Reformer

The British Museum under construction, 1845 (Illustrated London News)

In Europe, where industrialization was more advanced than in the U.S., Fuller hoped to find successful models of communities and institutions to prevent the expansion of poverty back home. During this time of steamships, railroads, telegraphs, and booming emigration to American cities, Judith Mattson Bean and Joel Myerson explain, “She envisions American culture as receiving not only people but seeds of thought and expression from other nations.” These “thoughts” could be cultural as well as social and political.

In Liverpool and Manchester, England, Fuller went to Mechanics Institutes where anyone (male or female) with 5 shillings could attend lectures, take courses, or see art exhibitions. In London, she reported on cultural and literary goings-on. In Paris, when she visited homes, hospitals, and day care centers for the sick children of the poor, she observed evening schools where boys were taught a trade. In her dispatches to the New-York Tribune, she recommended that America immediately adopt such measures.

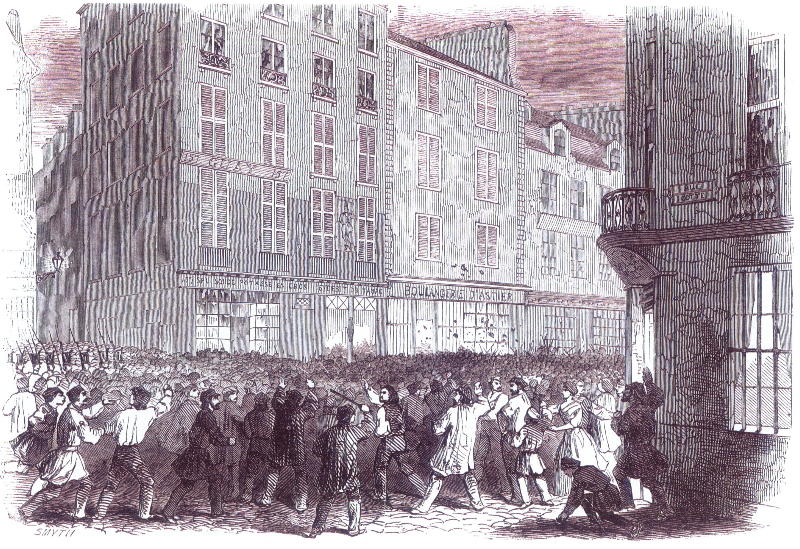

But it was the urban poverty of the slums that affected Fuller most of all, and the clear need for reform. In a dispatch from France she wrote, “The need of some radical measures of reform is not less strongly felt in France than elsewhere, and the time will come before long when such will be imperatively demanded.”

She also wrote, “To themselves be woe, who have eyes and see not, ears and hear not, the convulsions and sobs of injured Humanity.”

Two questions plagued Fuller’s mind: What was her role in what she was witnessing? What was America’s role?

As Joan von Mehren points out, after visiting Paris, “Every one of her columns now made some plea on behalf of its ‘injured Humanity.’” While the initial purpose of Fuller’s journey to Europe was “to seek useful ideas to transplant to the new world,” she was transformed by her experience into “a radical vocation to communicate the monstrous suffering and human waste of the historical movement.”

If there was any doubt in Fuller’s mind about her stature as an international voice, there was no doubt in the minds of her new European friends. Fuller’s reputation preceded her. They seemed to know she was destined to bridge the two continents and promote the reforms that were in their mutual interest. They embraced her.

In England, she renewed her acquaintance with social commentator Harriet Martineau, met the poet William Wordsworth, and the co-editors of the People’s Journal Mary and William Howitt (whose modern marriage she had described in Woman in the Nineteenth Century). She also met Giuseppe Mazzini, the legendary exiled Italian revolutionary about whom Fuller had written for the Tribune. She was drawn to his cause and became his confidante and secret messenger.

London slums, 1856

In Paris, Fuller met George Sand and Pierre Leroux, who invited her to publish work in their periodical La Revue Indépendante. She was introduced to the exiled Polish revolutionary and poet Adam Mickiewicz, who became a kind of spiritual guide.

Fuller was in her element, filled with a sense of purpose and armed with the skills and mechanism (the Tribune) to make a difference. But the best was yet to come—Italy.

Bread Riot in the Rue du Fauborg St. Antoine, Paris, 1846 (Illustrated London News)

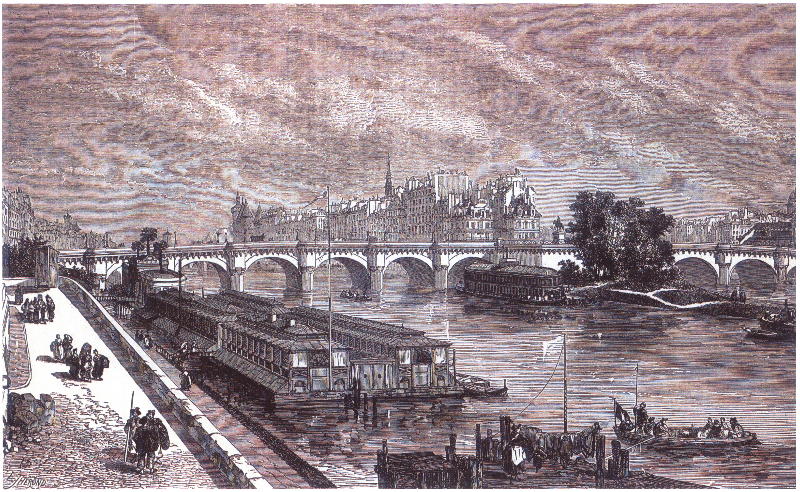

The Pont Neuf, Paris, 1845