Select a news topic from the list below, then select a news article to read.

Margaret Fuller Postage Stamp Nomination Letter

Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee

c/o Stamp Development

U. S. Postal Service

1735 North Lynn St., Suite 5013

Arlington, VA 22209-6432

March 26, 2009

Members of the Committee:

Despite the late notice, we hope you will consider an honorary stamp on behalf of MARGARET FULLER (1810-1850) to celebrate the bicentennial anniversary of her birth in 2010.

Despite a lack of formal education, Fuller became one of the leading minds of her generation. A founding member of the Transcendentalism movement, she was the first editor of their literary voice, The Dial. Her career as a journalist later brought her to New York, where she became the first woman to be a full-time book critic anywhere in the world. Her connection to Horace Greely’s New York Tribune next brought her to warn-torn Italy, where she became the first American woman to be an overseas correspondent as well as the first to serve during wartime. While overseas, she joined in the cause of Italian revolution.

By this time Fuller had already published Woman in the Nineteenth Century – a book considered by many to be the first major work of feminism in the United States. In it, she asked Americans to redefine gender roles by opening more doors for women. In particular, Fuller promoted access to higher education and political rights as well as employment opportunities. To further her message, she took it upon herself to help women who had been denied access to proper formal education by presenting a series of “Conversations” for women to discuss college-level topics.

Her interest in reform, however, was not wholly focused on women. She was also an ardent abolitionist, referring to the “cancer of slavery.” She also sought reform in prisons and called attention to those who were poverty-stricken. She drew attention to the Native Americans who had so recently been displaced and consider these people an important part of the nation’s heritage. In writing a book on Native Americans, she used the library at Harvard University for research – the first woman allowed to do so.

In the nineteenth century, Fuller was admired by the likes of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, George Eliot and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Awed by her assertiveness, Edgar Allan Poe came to believe that there were three types of people in the world: “Men, women, and Margaret Fuller.” After her tragic death by shipwreck in 1850, Fuller’s later admirers included Susan B. Anthony, who considered her the “precursor of the Women’s Rights agitation” and that she “possessed more influence upon the thoughts of America, than any woman previous to her time.”

For a woman of the nineteenth century, Margaret Fuller was clearly ahead of her time. Using both her voice and her pen, she attempted to redefine the roles of women and earn respect and equality for all Americans. Now, 200 years after the birth of Margaret Fuller, her messages still stand. We, the undersigned, represent only a small faction of people who believe her memory should be honored by the tribute of a federal postage stamp. Thank you for your consideration.

With sincerity and gratitude,

Representatives of the Margaret Fuller Bicentennial Committee

"By genius belonging to the world"

On May 23, I’ll follow my annual routine for that day: I’ll wait for the gates to open at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Mass., park in a Visitor spot, then head toward the hill about a quarter-mile on. I’ll take a right on Pyrola Path, pass by McGeorge Bundy’s simple headstone, and climb a small rise to the left. There, I’ll enter the Fuller family lot.

Yes, geodesic-dome inventor Bucky Fuller lies there, his gravestone etched with his most famous invention. He shares a marker with his wife, Anne Hewlett, most appropriate as they died within hours of each other a quarter-century ago. Seeing their headstone alone is worth the visit. But on this day, I’ll pay homage to a different family member, Bucky’s great-aunt, on her 199th birthday.

Become a Community Partner

The Margaret Fuller Bicentennial (MFB) is an opportunity to celebrate and learn about an extraordinary woman and continue her global vision of equality and human rights.

The Margaret Fuller Bicentennial Committee is a grassroots group of scholars, representatives of historical sites, commissions, organizations, and Unitarian Universalist ministers and lay people.

We invite your organization to join us as a Community Partner.

Community Partners are encouraged to use the MFB logo and will be recognized on the MFB website and other in publicity about the Bicentennial.

As a Community Partner of the Margaret Fuller Bicentennial (MFB), you agree to do any or all of the following:

Margaret Fuller's Books Online

- Conversations with Goethe in the Last Years of His Life (translated by MF into English)

- "The Great Lawsuit: Man vs. Men Woman vs. Women," published in the Dial magazine

- Summer on the Lakes, in 1843

- Woman in the Ninteenth Century and Kindred Papers Relating to the Sphere, Condition and Duties, of Woman.

Biography - Early Years

Early Years

Sarah Margaret Fuller was born May 23, 1810, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the first child of Timothy Fuller and Margaret Crane Fuller. She was named after her paternal grandmother and her mother; by the age of nine, however, she dropped "Sarah" and insisted on being called "Margaret". The Margaret Fuller House, in which she was born, is still standing. Her father taught Fuller to read and write at the age of three and a half, shortly after the couple's second daughter, Julia Adelaide, had died at the age of fourteen months. He offered her an education as rigorous as any boy's at the time and forbade her from reading the typical feminine fare such as etiquette books and sentimental novels. He incorporated Latin into his teaching shortly after the birth of the couple's son, Eugene, in May 1815, and soon she was translating simple passages from Virgil. During the day, young Margaret spent time with her mother, who taught her household chores and sewing. In 1817, her brother William Henry Fuller was born and her father was elected as a representative in the United States Congress. For the next eight years, he would spend four to six months of the year in Washington, D.C. At the age of 10, Fuller wrote a cryptic note which her father saved: "On the 23rd of May, 1810, was born one foredoomed to sorrow and pain, and like others to have misfortunes".

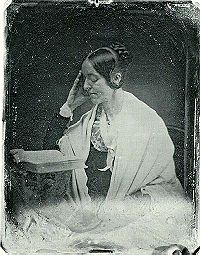

Photos

Some photos of Margaret Fuller.

Contact Us

Please contact us via e-mail: info [at] uuwr.org

The Margaret Fuller Bicentennial Committee has included:

Rev. Dorothy Emerson, Co-Chair

Laurie James

Emily Shield

Rev. Rosemarie Smurzynski

Rev. Elizabeth B. Stevens

Lisa Paul Streitfeld